Stretching from Chang-an (modern day Xian) in the east to shipping points on the Mediterranean and Black Seas, the Great Silk Road was a network of shifting caravan tracks passing through some of Asia's highest mountains and deserts. For centuries it formed the trade route through which not only valuable and exotic goods, but also ideas moved across continents.

Central Asia lies right in the middle of this epic route and Uzbek cities like Samarqand, Bukhara and Khiva prospered while providing trade facilities to caravans that converged here from both directions. The havoc wreaked by Genghiz Khan and Timur (Tamerlane) in the 13th and late 14th centuries respectively undermined the stability of the region and the importance of the Silk Road gradually declined. The discovery of maritime trade routes between Europe and Asia finally made the whole caravan route completely irrelevant and a string of cities on its path were abandoned. But some Uzbek cities have endured over the centuries and their names continue to evoke the romance of the Silk Road.

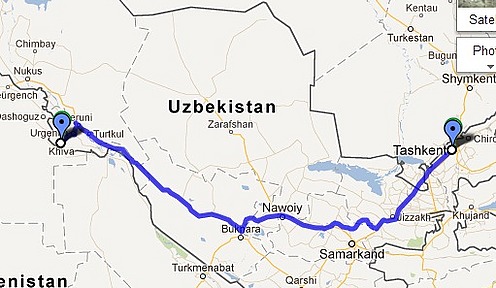

We started our exploration of Buyuk Ipak Yol'i , (Uzbek for the Great Silk Road) at Khiva which is located in the Khorezm province in western Uzbekistan. After a comfortable night's sleep on the overnight train from Tashkent to Urgench, we woke up to day breaking over the scrubby Kyzylkum desert. But it was not all bleakness as large tracts of desert have been converted into cotton fields. Urgench, the capital of Khorezm province, by itself has little to offer to a visitor but serves as a transport hub for Khiva 35 mms southwest and we had little trouble finding transport to take us there.

Until the 14th century Khiva was a minor fort and trading post on a side branch of the Silk Road. When the Uzbek Shaybanids moved into the decaying Timurid empire in the early 16th century, one branch founded a state in Khorezm and made Khiva their capital in 1592.

The town was famous for its long and brutal history as a slave trading post between the vast Kyzylkum and Karakum deserts. But it is somewhat difficult to conjure up the squalor and bustle associated with it when you visit Khiva today. And the reason for this is not because it has been destroyed completely. Quite the contrary. It is because the entire 3 sq. km walled city (called Ichon-Qala) has been turned into a squeaky clean 'city museum'! The Soviet Union undertook an aggressive conservation program here in the 1970s and ’80s, and consequently the historic areas were restored and cleaned up. While this makes Khiva a visual delightful, it also seems to somehow detract from its authenticity.

Ichon-Qala is densely packed with mosques, medressas and minarets. Some of the mosques are still functioning places of worship but many have been converted into museums. Some former medressas have been converted into hotels and restaurants but they are thoughtfully designed to blend in with their surroundings and don't appear out of place.

The walled city has four entrance gates, one in each cardinal direction. At the west gate is Kunha Ark, the Khiva ruler's fortress and residence that was first built in the 12th century. It includes a throne room, a mosque, a harem, barracks and stables. After walking through these, one is able to climb up a bastion that is set against the massive west wall to get a picture postcard view of Khiva.

Another gem is the Kalta Minor Minaret, an unfinished minaret that was begun in 1851 by Mohammed Amin Khan, who according to legend wanted to build a minaret so high he could see all the way to Bukhara. Unfortunately he died 1855 and it was never finished. But the huge base of the minaret and the beautiful tile decoration that covers it make it very distinctive.The town includes a mausoleum to Pahlavon Mahmud (Wrestler Mahmud) who was a poet, philosopher and legendary wrestler who became Khiva's patron saint. The revered mausoleum has beautiful tile work both on the sarcophagus and the walls and is set in a lovely courtyard.

The Juma Mosque has 218 wooden pillars support its roof. While it was rebuilt in the 18th century, many of the finely decorated pillars are from the original 10th century mosque. Another mosque, the Islam-Hoja mosque is also a striking building and the 57m tall minaret, with bands of lovely turquoise and red tiling is Uzbekistan’s highest. We were in and out of several of the medressas that now exhibits Khorezm handicrafts through the ages. They showcase fine woodcarving, metal work, jewelry, Uzbek and Turkmen carpets and stone carved with Arabic script.

The heart of Ichon-Qala is a pedestrian zone and the craftsmen and souvenir sellers who line the streets are neither intrusive nor pushy. This allowed us to watch them at work and examine their wares without being pressured into buying. We were specially intrigued by the ubiquitous sales of what looked like circular clothes brush with iron nails until we found out that they were used the stamp special designs on bread.

As we wandered around the narrow twisting alleyways, we would sometimes unexpectedly catch a glimpse of a richly decorated minaret and it would suddenly bring back some of the mystique associated with its glory days.

Google Maps Link

Comments