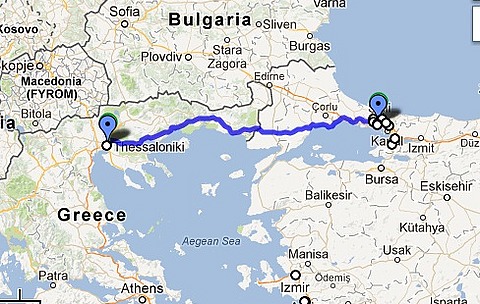

For all the talk about Asian Istanbul and European Istanbul across the Bosphorus, one does not feel any real difference between the two sides today. But arriving in Thessaloniki from Istanbul leaves one in no doubt that you are in a different continent. Some of this may have to do with Greece's current economic troubles, but here are a set of immediate first impressions:

- The smiles have disappeared and replaced with grimmer expressions

- More black and more leather clothing

- More style, less joy

- More tattoos and body piercings

- No one has heard of Mithun Chakraborty

- The locals are not curious about you at all

- The default morning drink is coffee, just a sip and one knew what one had been missing

- Groups of men of African descent selling watches and handbags on the street

- The signs on the streets and shops seem to be trigonometric formulae - Oh, wait - that is just Greek

Not so reassuring was the sight of garbage overflowing the bins in every street. The citizens were doing their bit by not littering and depositing their garbage in the bins. But austerity measures have obviously forced the city administration to cut back on their removal making for a wordless testament to the tough economic times of the day. We gave in to the enticing sight of outdoor seating at a creperie for our first Grecian meal and quickly decided to stay indoors going forward after being pestered by several peripatetic salesmen trying to sell you perfumes, handbags and other trinkets as well as those who simply wanted your money for nothing.

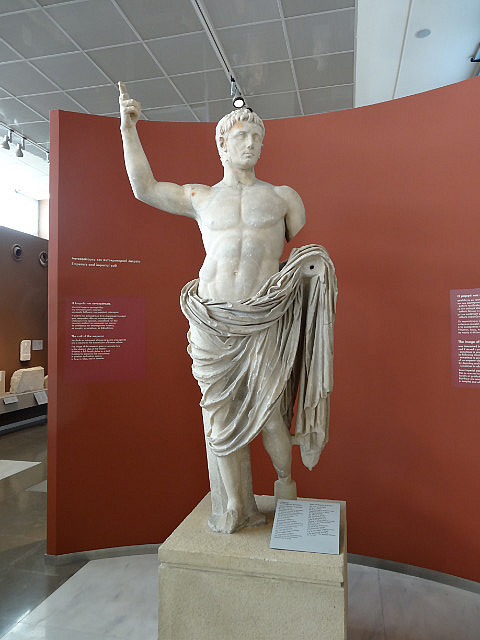

Thessaloniki's waterfront is the Thermaic Gulf, an arm of the Aegean Sea. Down by the water is the city's main landmark, the White Tower. A 12th century Byzantine fortification that was significantly reconstructed by the Ottomans to fortify the city's harbour, it was a notorious prison and scene of mass executions during the Ottoman rule. Greece gained control of Thessaloniki in 1912 and adopted it as the symbol of the city. It looked deserted on this early Monday morning and its museum was closed as were several other museums in the city. Exceptions to these were the two excellent museums that were open on Mondays and offered a combined discount. These were the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki and the Museum of Byzantine Culture. We made good use of our homeless state on our first morning in Greece by browsing through the latter, reserving the former for our second day. These provided valuable lessons in the history of the Greek province of Macedonia and served as a good introduction for the rest of our Grecian sojourn. The Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki houses some of the most important ancient Macedonian artifacts and exhibits from Macedon's prehistoric past, dating from the Neolithic to the Bronze age. The Museum of Byzantine Culture was awarded Council of Europe's museum prize in 2005. Apart from refreshing our recently acquired knowledge of Greek and Roman columns, this excellently laid out museum focused on burial customs and religious iconography over the various stages of the Byzantine era.

The number 50 bus starting at the White Tower covers all the city sites with a recorded English narration and this is augmented by live narration from a young woman on board. We were the only guests on board for most of the circuit on this late November morning - a sign of the low season and the economic low that Greece had gotten itself into after the euphoria of hosting the 2004 Olympics and winning the 2004 European Football championship. Not quite the hop-on hop-off deal that is the standard set by other European cities, but quite a bargain for 2 Euros. You are only allowed to complete one full circuit and cannot board from an earlier point. We intended to use it for an overview only and so it suited our plans perfectly. We particularly enjoyed its tour of Thessaloniki's Upper Town (Ano Poli) covering the Byzantine walls and traditional houses as it negotiated the narrow alleyways making impossible turns.

The two terraced Roman Agora (aka Forum) is located in a compact city square (After visiting these agoras, one can never look at a demolished city square the same way). Remnants of a small theatre and a lone standing column can be seen. Arches over a subterranean passage recalled our previous week's visit to Smyrna linking the two cities divided by the Aegean Sea but united with their shared past. The basement houses a very informative museum on the agora (which dates back to the 2nd century AD when it was in active use). Thessaloniki was one of the three cities visited by the Apostle Paul on the Balkan peninsula. He preached Christianity to the Greek speaking Jewish community there in the 1st century. The First Epistle to the Thessalonians written by him is the first written book of the New Testament. St. Paul's request to preach at the Agora's podium was denied by the pagan elements. The ascent of Theodosius II to the throne brought the days of the Agora to an end due to his outlawing paganism (yet another link to our previous week when we visited the Temple of Artemis outside Ephesus and learnt about the Christian mob that destroyed it following the Edict of Thessalonica).

Now that we were in Greece, we got to see a fair share of Greek Orthodox Churches with the familiar icons (Christ Pentakrator etc.). The most prominent church is the 5th century Church of Agios Dimitrios (named in honor of the city's patron saint). Born in the 4th century, he is one of the most important Orthodox military saints and is revered throughout the region. He was martyred under the orders of the Christian-persecuting Galerius. The martyrdom site is an underground crypt under the church. We managed to find the entrance to this crypt and explored the subterranean space underneath. The saint's relics are kept in a silver reliquary in the main church hall. After veneration as a saint, Demetrius was credited with defending Thessaloniki from various invasions by the Slavic peoples..

The nearby Alaja Imaret, an Ottoman mosque dating to the 15th century is now only used for cultural activities. It acquired its name, Alaja Imaret (multi-colored poorhouse) from the many-coloured, diamond-shaped stones used in the decoration of its minaret, and from the poorhouse(imaret) which stood next door to the mosque.

Thessaloniki was also home to the Sephardic Jews who were driven out of Spain by Isabella and Ferdinand in the 15th century. They settled in the Rogos neighbourhood, close to the Agora site. The area was subject to frequent epidemics and fires. It was completely burnt out in the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917, one of the city's defining moments in history. 50,000 Jews were rendered homeless forcing many of them to emigrate abroad. Thessaloniki also saw an influx of Greek refugees from Turkey after they lost the Greco-Turkish war of 1922. After this, Jews still made 20% of the city's population. The Nazis occupied Thessaloniki during WWII and sent 96% of its Jewish population to concentration camps. Today's Jewish population in the city is 1200.

The 8th century Agia Sophia does invite comparison with its much more famous (and impressive!) counterpart in Istanbul. It features a domed basilica much like its original counterpart. The dome features an image of the Ascension of Christ. Even this one was converted to mosque during Ottoman times, but was resanctified in 1913.

Contemporary restaurant and cafe culture thrives in the waterside neighbourhood of Ladadika.

Google Maps Link

Comments