We left Lahic on a rainy morning and caught the first marshrutka out from the village back to Ismayilli on the main Baku-Balakan highway. It filled up quickly with good natured regulars who greeted each other in a familiar manner and settled down for the ride into town. Along the way a large group of school children dressed in neat uniforms joined in and actually looked happy to be going to school! Before long a feisty old woman seated half way down the bus started talking loudly with the driver at the front of the bus. Other people starting joining the discussion and soon we had a raging debate going. We had no clue as to the subject of the discussion or the positions taken by the various people but judging by the laughter it evoked at regular intervals it seemed the entire bus found it quite entertaining. If only we had someone to translate in real time, we may have gained some really important insights into what seemed like an intense public debate.

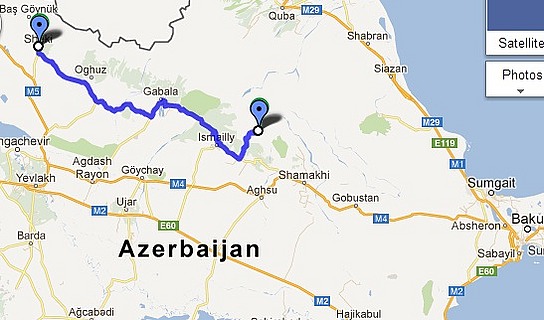

Once we got to Ismayilli, we found out that the bus to Qebele, our next transit point that would finally lead us to Sheki, left from a completely different bus stop. Seeing our confusion, a gentleman who seemed to be headed in the same direction asked us to follow him and we ended up walking at least a kilometer in steady rain. We waited impatiently for over an hour before a minibus bearing a Qebele signboard finally arrived and we were on our way. The road passes through an undulating landscape on the foothills of the Caucasus mountains, and the scenery is particularly pretty between İsmayıllı and Sheki.

Sheki was the capital of the khanate of Khan Haci Celebi in the 1700s when it was called Nukha. The khanate was ceded to Russia in 1805 but the town continued to flourish as a silk weaving town. It was an important junction on the caravan route between Baku and Tbilisi where it met the cross-mountain branch route to Dagestan. At its peak there were five working caravanserais here. One of the historic caravanserais has now been restored as is open to guests as the Karavansaray Hotel.

A steep cobbled street from the old town leads to the stone perimeter of a fortress complex. Inside the fortress are some of Sheki's main attractions of which the most interesting is the Khan's Palace. It was built in 1762 and though not impressive in size, the interior of the palace is decorated in extraordinarily colorful murals. The facade of the building is decorated with silvered stalactite vaulting and geometric patterns which is complemented by beautiful stained-glass windows. Visitors are allowed to tour the palace only in the company of a guide and unfortunately photography is prohibited inside the palace.

Another building in the complex has been set aside for workshops and studios of artists and craftsmen who are keeping traditional Azerbaijani arts and crafts alive. We were happy to visit several of these, observe experts at work. At a studio displaying traditional musical instruments, a young man played a few short pieces on the Tar (lute) for our benefit.

Higher up in the valley, approximately 5 kms north of Sheki is the small town of Kis (pronounced Kish). It was the original site of the khanate but Kis was obliterated by catastrophic floods in 1772 and the capital moved to Sheki. It is reputed to be the best place anywhere to learn about Caucasian Albania (not be confused with the contemporary Balkan Albania), the Christian nation that once covered most of northern Azerbaijan. A half hour ride on the marshrutka took us to the entrance of Kis village and we followed signs up even steeper cobbled streets to the round towered 12th century Albanian church.

Even before we entered the church we we were intrigued by the presence of a statue of Thor Heyerdahl (the Norwegian explorer) close to the entrance of the church. We found out that the church has been renovated with the help of the Norwegian government and has now been converted in to a museum. It was only when we started reading about the history of its renovation, that we began to see the connection between the two.

We learned that Heyerdahl had a particular interest in Azerbaijan's early history. He had made several visits to the country and was convinced that Norwegians (and other Scandinavians) can trace their roots back to Azerbaijan. According to Norwegian legend, the god Odin came from the land of Aser that lay east of the Black Sea and Heyerdahl theorized that Aser was in fact Azerbaijan. He used archeological evidence found in Kis to bolster his theory. Buried in the area in and around the church were skeletons of people much taller than current day Azerbaijanis. Study of the remains indicate that they had blond hair, much like current day Scandinavians. One of the museum staff explained to us that the average height of Azeris went down over time after mixing with other races in the region. Heyerdahl also used the petroglyphs of reed boats at Qobustan (which we had visited earlier) to support his case.

While this is one of his more controversial theories (and has been disputed by other scholars), it was interesting enough to Norwegians and encouraged the Norwegian Humanitarian Enterprise (supported by the Norwegian government) to take interest in studying and restoring the church. Whether historically correct or not, purely on account of his theory, Thor Heyerdahl is a much admired figure in Azerbaijan.

Google Maps Link

Comments